- Offerings

- Tools & Platforms

Tools & Calculators

- Open API

- Calculators

- SIP Calculator

- CAGR Calculator

- Compound Interest Calculator

- FD Calculator

- RD Calculator

- EPF Calculator

- Retirement Calculator

- HDFC SIP Calculator

- Mutual Fund Return Calculator

- Lumpsum Calculator

- Step Up SIP Calculator

- ETF SIP Calculator

- Brokerage Calculator

- Equity Margin Calculator

- SWP Calculator

- EMI Calculator

- MTF Calculator

- Pricing

- SKY Learn

- Mutual Funds

- Margin Trading

- Financial Planning

- Personal Finance

- Share Trading

- IPO

- Derivatives

- Currencies

- Intraday Trading

- Trading Strategies

- Demat Account

- Commodity

- ETF

Why invest in the stock market? Know the Benefits of stock market investment

By HDFC SKY | Updated at: Jun 2, 2025 11:35 AM IST

When it comes to investing (or not investing) in equities, everyone has different views. Some stay away from it because they think it’s gambling. Others, their perspective shaped by films or perhaps their own experiences, say it is manipulated by a handful of people.

Those in favour of investing in stocks think it’s an avenue to make easy money. They see prices going up and down wildly in a matter of days or weeks – 5-10-20% — and think there will be a way to figure out what causes the prices to move, and you can make as much or more in a short time as you would in a year in an FD.

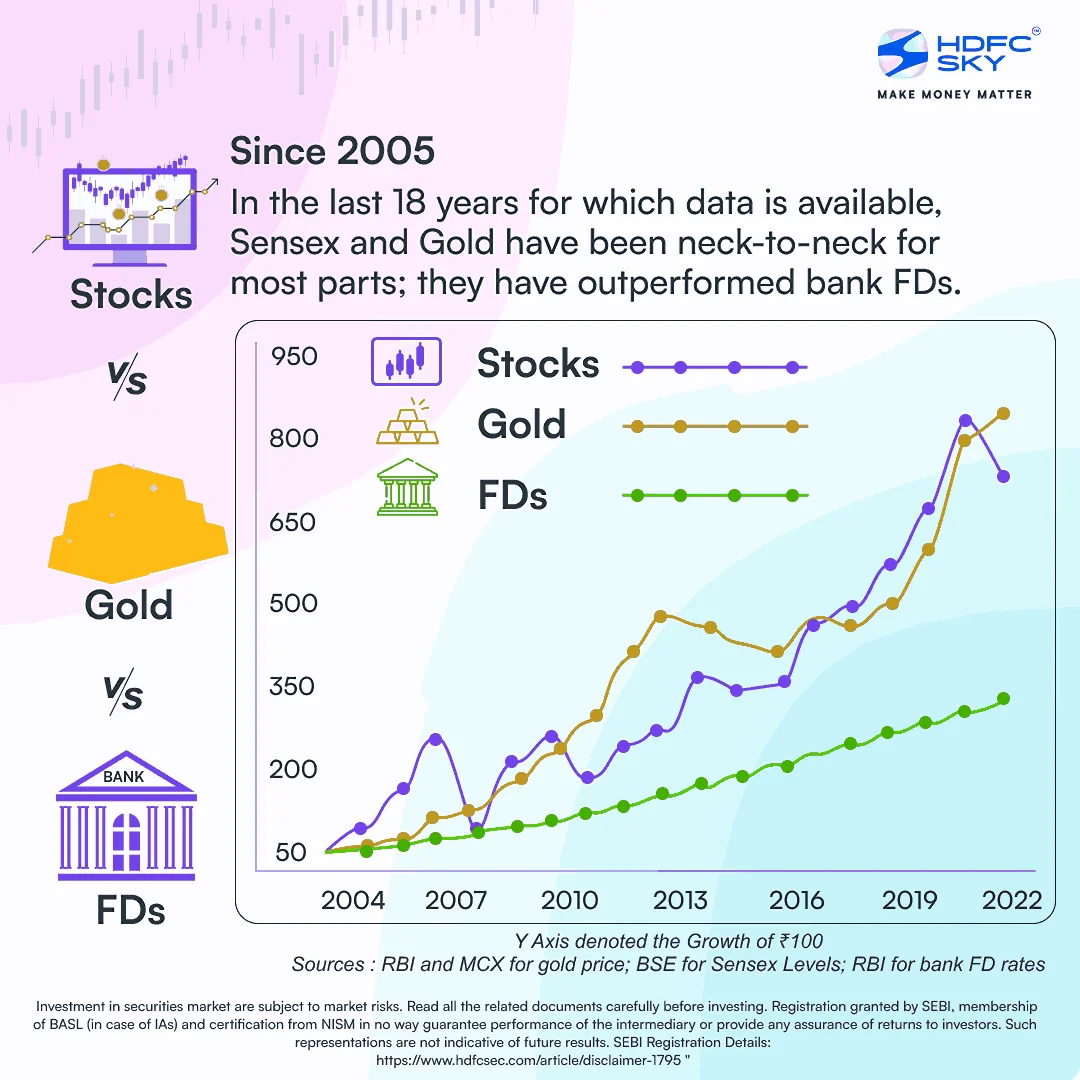

And then there’s the more sophisticated explanation: stocks do better than other asset classes over the long term. If you ask a financial advisor why you should invest in stocks, they will hold up the long-term chart of the Sensex in front of you. 800 in 1990. 4,000 in 2000. 20,000 in 2010. 50,000 in 2020. Pretty cool, right? See the power of equities? They always go up. “If you’re bullish on the Indian economy, the best way to bet on it is by investing in stocks”, your advisor will say.

But let’s go back a little bit: if you were an adult in 1990, or 2000 or 2010, could you imagine that the Sensex will be up anywhere between 2.5 times to 5 times over the next 10 years? Will you say with any reasonable certainty today that the Sensex will be anywhere between 1.25 lakh to 3 lakh in 2030?

There is a piece of math that will clear this up, and it’s not difficult to understand. Two pieces of math, actually.

Math 1: The pandemic and the restaurant

Imagine it’s December 2019 and your friend has recently opened a restaurant, which has started doing well for itself. You think it will be a great decision to become a partner in the business. You know the business’ math. The restaurant has daily revenue of Rs 5 lakh, and a 50% profit margin (Rs 2.5 lakh net profit). This means a yearly revenue of Rs 18 crore and a profit of Rs 9 crore.

He says he will give you 5% stake in the business for Rs 5 crore. You run the numbers in your head. He is valuing his business at Rs 100 crore when he is making Rs 9 crore in profits. Your friend says he is planning to open another restaurant and the profits will soon double. (Assuming you have the money) you will either accept or reject the deal. Let’s say you did not bite even though you thought your friend was making a reasonable ask.

Fast forward to June 2020, and it’s three months into the lockdown and things are looking bleak. Your friend now again makes you an offer. A 20% stake in the business for Rs 5 crore. He desperately needs the money to keep the business afloat. The valuation has crashed to Rs 25 crore. You think the pandemic will be over at some point on the other. What’s even better. The restaurant owns the property on which it operates and even in a worst-case scenario, it can be sold for Rs 5 crore. You bite the bullet. A year later, the business has rebounded. Your restaurant is again expecting to make a reasonable profit this year.

The math that you need to keep in mind is all businesses have some value till as long as they remain afloat. Within months, the owner of the restaurant was willing to reduce its value by 75% when a year later, things were nearly the same as they used to be. And that, at a particular price, there will always be takers.

There’s one last thing you need to keep in mind before we close this example, and it’s the most important point. Your friend, the restaurant owner, was in December 2019, demanding a price-to-earnings ratio of a little more than 10 times. (Rs 100 crore valuation for a business that makes Rs 9 crore profit.) Six months later, this PE ratio stood at as little as 2.5 times.

Math 2: India’s GDP

India is a fast-growing economy and will remain so for a long time. Why? The reasons are many, which we need not go into but the simplest one is that on average, we are still a country that has among the lowest per-capita GDP in the world. This gives us inherent cost advantages, which causes an upward adjustment.

Now, we will make certain assumptions. Since 1990, India has grown at an average of 6%. Under-developed and fast-growing economies also tend to have high inflation. (See insights section for explanation.) On average, inflation has remained at 5%.

This translates to an average nominal GDP growth of (6+5=) 11%. Hold on, you will say. Why are we adding inflation to growth? For that, you will have to read the Insights section alongside (Last one, we promise).

Assuming an economy grows at 11%, is it too much to assume that its best companies run by some of the most talented managers will be able to grow their revenues and profits a little more than 11%. How about 15-16%?

Voila. That’s exactly how much corporate profits have grown over the past 30 years.

The long-term math

In the short term, stocks, or any index like the Sensex, will go up and it will go down, but the underlying earnings pool of the companies tends to grow over time.

And as we discussed in the restaurant example, the valuation (or the PE ratio) we assign to these companies will be high (December 2019) or low (June 2020).

But if you want to know where the Sensex will be in 2030? Take the current earnings per share of the index: Rs 2,100 currently. (This is nothing, but the overall profit made by all the companies in the index divided by the number of shares they have.) Put it in a CAGR (Compounded Annual Growth Rate) calculator, implying 15% yearly growth. You arrive at Rs 8,500. Now multiply this number by any number between 12 and 30, which is the PE ratio investors are willing to pay for Indian companies. Where will the Sensex be? Anywhere between 1 lakh to 2.5 lakh.